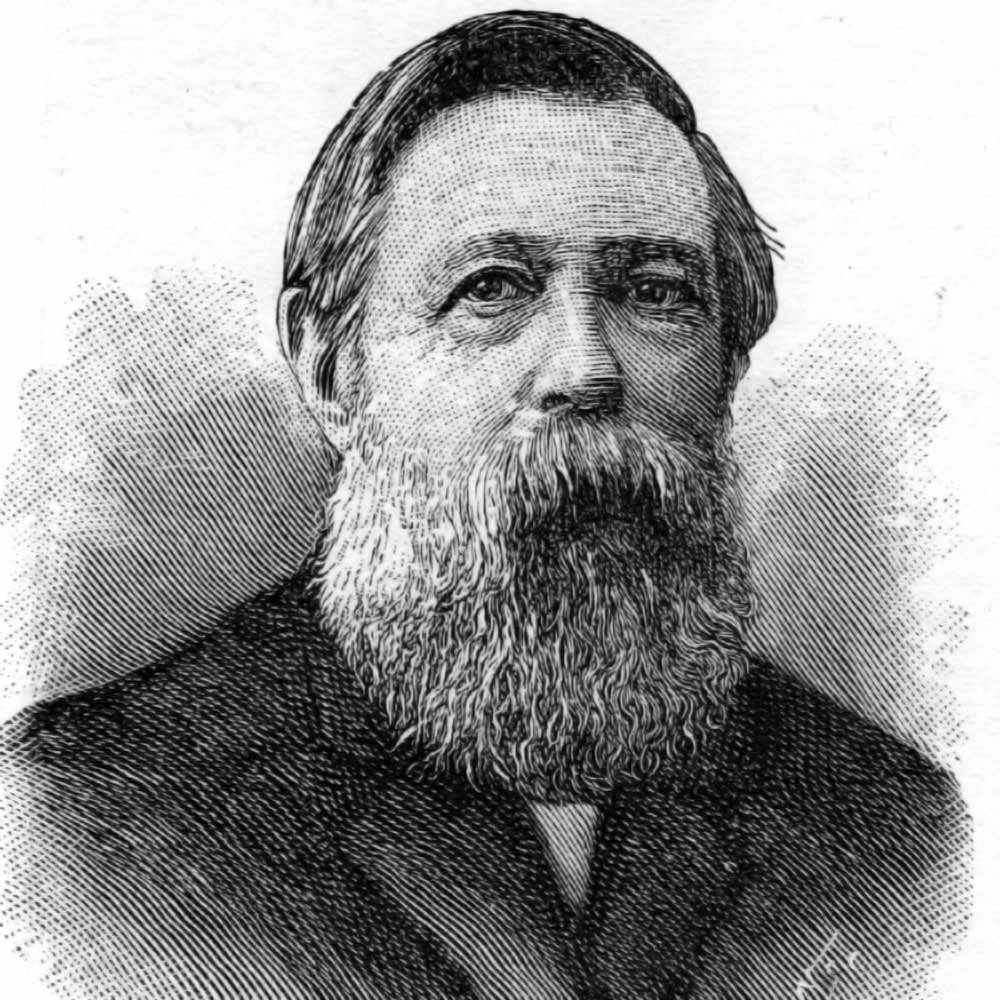

Radicalized in school, he decided on a different path for his life’s purpose. Yet Engels himself was of the bourgeoisie, his father owning textile factories in both Britain and Germany.

The horrors that he must have witnessed obviously changed the man, as he reserves his most forceful language for the English bourgeoisie, those who put children in mines, calling them “incurably debased by selfishness, so corroded within, so incapable of progress.” Not only that - they were “deeply demoralized,” cynical, and cold. He painstakingly recorded the litany of horrific diseases these people were subject to, with many passages on painful intestinal illness, women losing pregnancies to miscarriage, and on childhood physical development arrested due to back-breaking work. He witnessed firsthand the miserable conditions of all sections of the proletariat he could find access to. Thirty-five years before, Engels published The Condition of the Working Class in England, written from his personal observations as he was shepherded through Manchester by his partner, Fenian organizer Mary Burns. This belies a focus on the individual as the fulcrum of history and reveals that this kind of socialism is rooted in utopianism, not the world.Įngels did not come to this criticism of utopianism by accident. In Socialism, Utopian and Scientific, Engels denounces the approach to socialism he describes as “ascetic” and “denouncing all the pleasures in life.” It is a religion he describes, something that seeks to abolish all ills in society at once, as if the only thing standing in the way of liberation for all humankind was simply going around and changing the minds of those in power. What can we learn from the work of Frederick Engels 200 years after his birth? Perhaps we can speak of what compelled this author to join the Communist Party to begin with - a desire to struggle for socialism in the world as it is today.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)